Thursday, June 28, 2007

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

An Assist from Dr. Harold Vonachen

I have Pete Vonachen’s father to thank for my existence and the fact that it is taking place in Peoria. Well, he at least deserves a little bit of the credit.

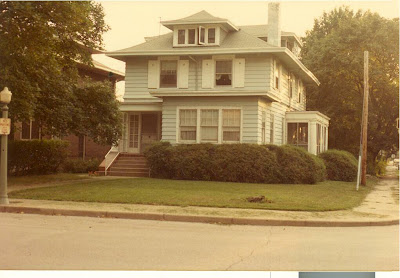

Pete’s dad, Harold, was a physician. So was his uncle John, who lived with his wife Isabelle and their four children, Molly, Carol, Betty, and Bob at 841 N. Maplewood from 1918 to 1945. John was the first pediatrician in Peoria and one of the first in the state. “I remember being in your old home many, many times,” said Pete. “It was a great house.”

Before he became the medical director at Caterpillar, Harold had a general practice and was also the doctor for the children who lived at Guardian Angel Orphanage on Heading Avenue. Sometimes he asked his brother John for help.

Both Pete, who has an amazing memory, and my dad contributed details to the following story.

My dad lived in Mt. Vernon, Illinois, where, as a young man, he became a pretty good athlete. In high school, he triple-lettered in baseball, basketball, and football. As center, he was voted the most valuable player on the Mt. Vernon Rams football team.

But it was on the basketball court where my dad and his teammates had their greatest success. In 1949 and 1950, the Mt. Vernon Rams won the Illinois State Basketball Tournament, going undefeated in ’50. And this was back when there was only one class for high school athletics in Illinois.

The starting players on the team, including my dad, received attention from colleges wanting to recruit them. The team’s star, Max Hooper, who was recently honored as one of the 100 top high school basketball players in Illinois history, was going to the University of Illinois. My dad decided he would go there too.

But that was before Dr. Harold Vonachen and a couple of his friends paid a visit to Mt. Vernon. Dr. Vonachen was very involved in the Bradley boosters club. He and his friends made the drive from Peoria to Mt. Vernon that in that day had to be close to six hours.

They came to town in a big black sedan. Dr. Vonachen handed the keys to my dad and his teammate John Riley and said, “Here boys, take the car for a ride. We want to talk to your parents.”

After the meeting, my dad’s parents suggested he check out Bradley. He had never heard of Peoria, much less Bradley, but he made a campus visit. And he loved what he saw. “The campus was beautiful and so much more personal than Illinois.”

He came to Bradley, majored in economics, pledged Sigma Chi, and became a starter on the basketball team, which placed second in the NCAA Tournament in 1954. While he was a student, Harold Vonachen was his physician.

My dad went on to receive a master’s in counseling at Bradley and spent his entire career working in administration at the Univeristy. He met my mom, who lived in central Illinois, and in 1961 the first of their five children were born.

And it all got its start because of Pete Vonachen’s dad. Thanks Dr. Vonachen

Pete’s dad, Harold, was a physician. So was his uncle John, who lived with his wife Isabelle and their four children, Molly, Carol, Betty, and Bob at 841 N. Maplewood from 1918 to 1945. John was the first pediatrician in Peoria and one of the first in the state. “I remember being in your old home many, many times,” said Pete. “It was a great house.”

Before he became the medical director at Caterpillar, Harold had a general practice and was also the doctor for the children who lived at Guardian Angel Orphanage on Heading Avenue. Sometimes he asked his brother John for help.

Both Pete, who has an amazing memory, and my dad contributed details to the following story.

My dad lived in Mt. Vernon, Illinois, where, as a young man, he became a pretty good athlete. In high school, he triple-lettered in baseball, basketball, and football. As center, he was voted the most valuable player on the Mt. Vernon Rams football team.

But it was on the basketball court where my dad and his teammates had their greatest success. In 1949 and 1950, the Mt. Vernon Rams won the Illinois State Basketball Tournament, going undefeated in ’50. And this was back when there was only one class for high school athletics in Illinois.

The starting players on the team, including my dad, received attention from colleges wanting to recruit them. The team’s star, Max Hooper, who was recently honored as one of the 100 top high school basketball players in Illinois history, was going to the University of Illinois. My dad decided he would go there too.

But that was before Dr. Harold Vonachen and a couple of his friends paid a visit to Mt. Vernon. Dr. Vonachen was very involved in the Bradley boosters club. He and his friends made the drive from Peoria to Mt. Vernon that in that day had to be close to six hours.

They came to town in a big black sedan. Dr. Vonachen handed the keys to my dad and his teammate John Riley and said, “Here boys, take the car for a ride. We want to talk to your parents.”

After the meeting, my dad’s parents suggested he check out Bradley. He had never heard of Peoria, much less Bradley, but he made a campus visit. And he loved what he saw. “The campus was beautiful and so much more personal than Illinois.”

He came to Bradley, majored in economics, pledged Sigma Chi, and became a starter on the basketball team, which placed second in the NCAA Tournament in 1954. While he was a student, Harold Vonachen was his physician.

My dad went on to receive a master’s in counseling at Bradley and spent his entire career working in administration at the Univeristy. He met my mom, who lived in central Illinois, and in 1961 the first of their five children were born.

And it all got its start because of Pete Vonachen’s dad. Thanks Dr. Vonachen

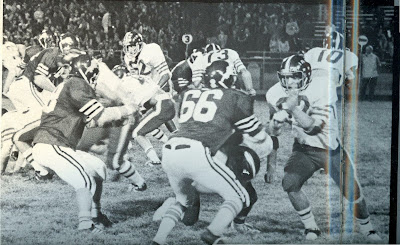

The top picture is of the 1954 Mt. Vernon Rams, who won the Illinois High School Basketball Championship. My dad is number 46. The bottom picture, from the Peoria Journal Star, shows the happy, victorious Braves after they defeated the Oklahoma City Chiefs, a victory that won them a berth in the 1954 NCAA Tournament.

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Pickin' the Winners on Maplewood

Orville Nothdurft, the Dean of Admissions at Bradley University for 25 years in the sixties and seventies, lived in the 900 block of Maplewood. His former home was the second to last to be leveled on this block.

After the Nothdurft’s moved from this home, Bradley English professor Peter Dusenberry and his family lived in the house for 23 years. “Mim Orville was very short woman,” said Dr. Dusenberry. “One of the Nothdurft daughters was a carpenter and she made all the counters and cabinets lower,” something the Dusenberry’s had to change when the house became theirs in 1984.

When I would walk to school, I remember seeing Mr. Nothdurft in his dark suit, walking across Bradley Avenue to his office in Swords Hall. He always had a friendly smile and a greeting. My dad, who early in his career at Bradley was the Assistant Dean of Students, was friends with Orville.

Dad, Mr. Northdurft, Les Tucker, the Dean of Students, and Doc Norton, the Dean of Men and head of the Speech Department formed the disciplinary committee, which started meeting in 1959-60. The four men were big Bradley basketball fans and after they dealt with whatever issues misbehaving students presented them, talk turned to the Braves.

To make things interesting, the four men created a friendly contest. Before Bradley games, they would each predict what they thought the final score of the game would be. A complicated—to my mind—scoring procedure was developed and at the end of the season, the fellow who earned the most points through his predicting prowess was declared the Bradley Basketball Top Prognosticator. His name was engraved on the plaque pictured above. The plaque only goes until 1977, but the contest continued into the early 90’s.

I remember many times my dad phoning in his prediction to whomever’s turn it was to track the scores. I would ask him his prediction and was always disappointed when he didn’t pick Bradley. According to my dad’s recollections, three times in the history of the contest one of the men correctly predicted the final score of both teams, the equivalent of a prognosticating hole in one.

Orville Nothdurft was a wonderful man, educator, and promoter of youth athletics. He died in 2001. In 2002, my dad received the Orville Nothdurft Lifetime Achievement Award, for service by a former Bradley student/athlete to his profession and the community. I know it is one of the biggest honors he has ever received.

When I would walk to school, I remember seeing Mr. Nothdurft in his dark suit, walking across Bradley Avenue to his office in Swords Hall. He always had a friendly smile and a greeting. My dad, who early in his career at Bradley was the Assistant Dean of Students, was friends with Orville.

Dad, Mr. Northdurft, Les Tucker, the Dean of Students, and Doc Norton, the Dean of Men and head of the Speech Department formed the disciplinary committee, which started meeting in 1959-60. The four men were big Bradley basketball fans and after they dealt with whatever issues misbehaving students presented them, talk turned to the Braves.

To make things interesting, the four men created a friendly contest. Before Bradley games, they would each predict what they thought the final score of the game would be. A complicated—to my mind—scoring procedure was developed and at the end of the season, the fellow who earned the most points through his predicting prowess was declared the Bradley Basketball Top Prognosticator. His name was engraved on the plaque pictured above. The plaque only goes until 1977, but the contest continued into the early 90’s.

I remember many times my dad phoning in his prediction to whomever’s turn it was to track the scores. I would ask him his prediction and was always disappointed when he didn’t pick Bradley. According to my dad’s recollections, three times in the history of the contest one of the men correctly predicted the final score of both teams, the equivalent of a prognosticating hole in one.

Orville Nothdurft was a wonderful man, educator, and promoter of youth athletics. He died in 2001. In 2002, my dad received the Orville Nothdurft Lifetime Achievement Award, for service by a former Bradley student/athlete to his profession and the community. I know it is one of the biggest honors he has ever received.

Friday, June 22, 2007

The 900 Block of Maplewood

In this trip through the dimly lit tunnels of my memory, I have been almost completely neglecting the 900 block of Maplewood. Actually, I have been mainly neglecting the experiences of everyone except me—and a few of my family members. Ah, the self-absorbed dangers of sitting down behind a computer with memories to burn.

Anyway, as to the 900 hundred block of Maplewood, my family also lived on this block for four years. My newlywed parents moved into the green shingled house on the corner of Main and Maplewood, 931 N. Maplewood, in 1960. The house was owned by Bradley, and my mom and dad paid $75 a month in rent. This house isn't part of Bradley University's current demolition project as it was knocked down years ago and turned into a grassy lot.

Anyway, as to the 900 hundred block of Maplewood, my family also lived on this block for four years. My newlywed parents moved into the green shingled house on the corner of Main and Maplewood, 931 N. Maplewood, in 1960. The house was owned by Bradley, and my mom and dad paid $75 a month in rent. This house isn't part of Bradley University's current demolition project as it was knocked down years ago and turned into a grassy lot.

I and my brother Jim were both born while we lived in this house. The memories from this time are pretty hazy, but I have a few.

Our next door neighbors, the Peyers, had beautiful rose bushes, which Mr. Peyer faithfully cultivated. One day, he gave me a rose, which is undoubtedly the first flower I ever received from a man.

The school crossing guards for Main Street stowed their flags on our front porch. How I coveted those flags! My mother was very adamant about not letting us touch them, though. One day, she relented, and we have pictures of my brother and me delightedly frolicking with the flags.

In December 1964, on my brother’s second birthday, we moved down the block to 841 N. Maplewood. Later that month, Mel and Evelyn Novak, who lived in the middle of the 900 block, had a holiday open house. Evelyn was the secretary for Cam Prim, who was then the Dean of Women at Bradley. Mrs. Novak had all these beautiful and intricately-made hors d’oeuvres set on the coffee and end tables throughout the house. It was with horror that my mom watched my brother Jim go around to the tables and pop many, many of these exquisite appetizers into his mouth. They were a little too low to the ground and a little too perfectly sized for a two-year-old’s fingers.

Mrs. Novak was just one of many Bradley employees who lived on Maplewood through the years. I’ll talk some more about a couple of them in my next post.

Peoria Journal Star sports editor Kirk Wessler mentions some of these Bradley folks in his wonderful June 22, 2007 column reminiscing about his childhood on Maplewood. He remembers the football games and the great Homecoming celebrations with all the house decorations. I can’t really recollect those times and the wish to do so, as well as what some would call a perverse desire to have come of age in the sixties, caused me to remark to my husband, who did grow up during those days, that I’d like to have been born about a decade earlier.

“So you wish you were 55 now?” he responded.

Well, I’m sure 55 will be fabulous when it gets here, but not exactly, and I guess you can’t have one without the other.

Our next door neighbors, the Peyers, had beautiful rose bushes, which Mr. Peyer faithfully cultivated. One day, he gave me a rose, which is undoubtedly the first flower I ever received from a man.

The school crossing guards for Main Street stowed their flags on our front porch. How I coveted those flags! My mother was very adamant about not letting us touch them, though. One day, she relented, and we have pictures of my brother and me delightedly frolicking with the flags.

In December 1964, on my brother’s second birthday, we moved down the block to 841 N. Maplewood. Later that month, Mel and Evelyn Novak, who lived in the middle of the 900 block, had a holiday open house. Evelyn was the secretary for Cam Prim, who was then the Dean of Women at Bradley. Mrs. Novak had all these beautiful and intricately-made hors d’oeuvres set on the coffee and end tables throughout the house. It was with horror that my mom watched my brother Jim go around to the tables and pop many, many of these exquisite appetizers into his mouth. They were a little too low to the ground and a little too perfectly sized for a two-year-old’s fingers.

Mrs. Novak was just one of many Bradley employees who lived on Maplewood through the years. I’ll talk some more about a couple of them in my next post.

Peoria Journal Star sports editor Kirk Wessler mentions some of these Bradley folks in his wonderful June 22, 2007 column reminiscing about his childhood on Maplewood. He remembers the football games and the great Homecoming celebrations with all the house decorations. I can’t really recollect those times and the wish to do so, as well as what some would call a perverse desire to have come of age in the sixties, caused me to remark to my husband, who did grow up during those days, that I’d like to have been born about a decade earlier.

“So you wish you were 55 now?” he responded.

Well, I’m sure 55 will be fabulous when it gets here, but not exactly, and I guess you can’t have one without the other.

My mom, brother, and I standing in the back yard at 931 N. Maplewood. My face reflects the unadultered glee I was feeling with the chance to hold the flag.

My dad holding me outside the house at 931 N. Maplewood.

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

"They Say It's Your Birthday. . ."

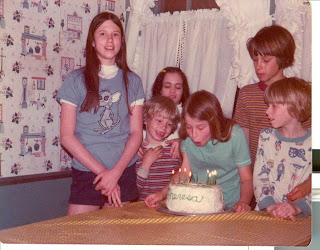

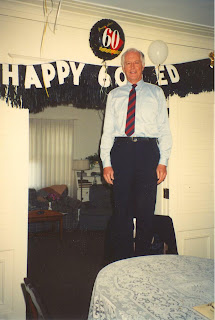

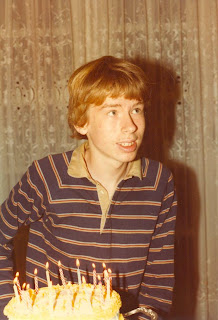

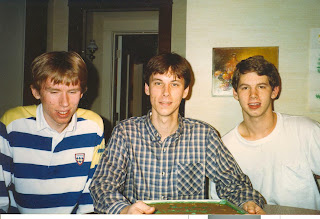

According to the cosmic calculator, I wonder how many birthdays have been celebrated on Maplewood. If our family’s photo albums are any indication, the general answer is a lot. A couple of comments on the photo montage with this post:

Do any one-year-olds have fun at their own birthday parties?

Apparently my dad and I like to stand on chairs on our birthdays.

My mom, who was so good about celebrating and photographing other people’s birthdays, had no picture of her own birthday and I had to make due with a picture of her cutting someone else’s cake.

As a non birthday-related aside on pictures that didn’t make the cut, why didn’t someone tell me how awful my various hairstyles were? In the same vein, why is it that things we think look so good at the time, we recognize as hideous years later? Evolved taste? Some sociologist needs to do a study.

Do any one-year-olds have fun at their own birthday parties?

Apparently my dad and I like to stand on chairs on our birthdays.

My mom, who was so good about celebrating and photographing other people’s birthdays, had no picture of her own birthday and I had to make due with a picture of her cutting someone else’s cake.

As a non birthday-related aside on pictures that didn’t make the cut, why didn’t someone tell me how awful my various hairstyles were? In the same vein, why is it that things we think look so good at the time, we recognize as hideous years later? Evolved taste? Some sociologist needs to do a study.

Monday, June 18, 2007

Destruction and Debris on a Sunny Day

For the past week, I’ve been taking my four-year-old son to bright, summery Lakeview pool for swimming lessons. There is nothing like enthusiastic, competent, 17-year-old girls who are good with kids to renew one’s faith in humankind. While I keep one eye on my son, dogpaddling in the clear, sparkling water with a noodle under his arms, the other’s on a book of essays, I Could Tell You Stories: Sojourns in the Land of Memory by Patricia Hampl.

Some of her writings don’t exactly match the sunny, good times vibe of the day, with pieces about Polish poet and writer Czeslaw Milosz, who speaks of “looking into the hells of our century” (the 20th) and Jewish/Catholic saint Edith Stein, a victim of the hell known as Auschwitz. “Memory is not just commemoration;” writes Hampl, “it is ethical power.”

It is a strange thing to be reading about such things while sitting by a pool, but good too. Perhaps this type of life where kids get to have swimming lessons can triumph over the kind of life where hatred spawned the Holocaust.

To continue my juxtaposing ways, I drive over to Maplewood to look at the destruction/progress on this radiant day.

The 800 and 900 blocks of Maplewood now look like a tornado or a war has hit them. Several of the houses are completely gone and others have been ravaged for what is valuable. As I look at this process, two metaphors leap to mind, one cup-half-empty and the other cup-half-full. The cranes, work crews, people going in and out of the houses remind me of vultures picking through the remains. On the other hand, when I look inside the glassless windows of my old house and see that the radiators and fireplace are gone, I tell myself that our house is like an organ donor and parts of it will live on in other homes.

The above paragraph begs the question, “Why are you continuing to drive by the neighborhood when it’s such a painful sight?” The whole process is like a slow motion death penalty for these houses.

The only answer I can give is that it’s to bear witness. I think there is inherent value in observing and describing events, even when they are depressing and register lightly on the historical scale. Hampl writes, “If we refuse to do the work of creating this personal version of the past, someone else will do it for us.”

For me, it would be even worse if this neighborhood was being eliminated with no one watching. I appreciate the coverage of this subject by PJS sports editor, blogger, and former Maplewood resident Kirk Wessler and blogger, Peoria, Illinoisian.

Some of her writings don’t exactly match the sunny, good times vibe of the day, with pieces about Polish poet and writer Czeslaw Milosz, who speaks of “looking into the hells of our century” (the 20th) and Jewish/Catholic saint Edith Stein, a victim of the hell known as Auschwitz. “Memory is not just commemoration;” writes Hampl, “it is ethical power.”

It is a strange thing to be reading about such things while sitting by a pool, but good too. Perhaps this type of life where kids get to have swimming lessons can triumph over the kind of life where hatred spawned the Holocaust.

To continue my juxtaposing ways, I drive over to Maplewood to look at the destruction/progress on this radiant day.

The 800 and 900 blocks of Maplewood now look like a tornado or a war has hit them. Several of the houses are completely gone and others have been ravaged for what is valuable. As I look at this process, two metaphors leap to mind, one cup-half-empty and the other cup-half-full. The cranes, work crews, people going in and out of the houses remind me of vultures picking through the remains. On the other hand, when I look inside the glassless windows of my old house and see that the radiators and fireplace are gone, I tell myself that our house is like an organ donor and parts of it will live on in other homes.

The above paragraph begs the question, “Why are you continuing to drive by the neighborhood when it’s such a painful sight?” The whole process is like a slow motion death penalty for these houses.

The only answer I can give is that it’s to bear witness. I think there is inherent value in observing and describing events, even when they are depressing and register lightly on the historical scale. Hampl writes, “If we refuse to do the work of creating this personal version of the past, someone else will do it for us.”

For me, it would be even worse if this neighborhood was being eliminated with no one watching. I appreciate the coverage of this subject by PJS sports editor, blogger, and former Maplewood resident Kirk Wessler and blogger, Peoria, Illinoisian.

Wednesday, June 13, 2007

What's a college?

My dad used to shave in the downstairs bathroom. This bathroom had two doors, one by the sink, opening onto the family room and one opposite the toilet, leading to the kitchen. My dad is 6’3” and he would have to bend his knees to see himself in the mirror.

One morning as he went through this daily ritual, my youngest brother, Mike, asked him, “Dad, what’s a college?”

As my dad continued running the razor over his face, he replied, “You walk through one every day.”

One morning as he went through this daily ritual, my youngest brother, Mike, asked him, “Dad, what’s a college?”

As my dad continued running the razor over his face, he replied, “You walk through one every day.”

This is the way it was for us with Bradley University when we were kids: our dad worked there and we walked through the campus to school. We lived across the street from the university, and if familiarity didn’t breed contempt with me, it surely dimmed the mystique of the place. Bradley was so much a part of our day-to-day lives that we didn’t really think about it that much. It was just there.

My dad worked in at least three different buildings on the campus during his tenure as Dean of Men, later renamed to the Director of Residential Life and the Judicial System. Doesn’t that change of title tell you a lot about the evolution in society, for better and worse? Through his almost 40 year career, he had offices in Bradley Hall, Swords Hall, and Sisson Hall. I don’t remember ever stopping in to see my dad at work, although one day when I was in junior high, in a cheesy grade school exercise, my friends and I polled some of the Bradley students as to what they thought of my dad. He got good reviews.

My memories of walking through the Bradley campus are specific, yet mundane: the wide, shallow steps between Bradley Hall and Westlake that led from Glenwood to the main quad; the impossibly steep wheelchair ramp between Westlake and the library; the “hills” in front of University Hall on Bradley; walking through the Swords Hall parking lot and marveling at the domed, space ship like appearance of the green house. A landmark day for us grade school kids was when the Sweet Shop, with its fancy candy, opened in the Student Center.

I remember the first time I noticed the two monstrous-looking appendages on the roof of Bradley Hall. “What are those?” I asked my father, shuddering. “Those are gargoyles,” he said. “They scare away the evil spirits.” A revelation: monsters for good.

The gargoyles are part of the gothic design of Bradley’s first two buildings, Bradley Hall and Westlake Hall. Bradley Polytechnic Institute was planned with input from William Raney Harper, the president of the University of Chicago, who was a member of Bradley’s original board of trustees. Bradley’s buildings look similar in style to those of the University of Chicago.

We soaked in the Bradley campus atmosphere as we walked to school. Any more, middle and upper class kids don’t seem to walk to school as much. My sister, Theresa, a Bradley grad, and her family live in Oak Park. The neighborhoods in this tree-filled, village-like suburb adjacent to Chicago, remind me of the neighborhoods of the West Bluff, albeit with vastly higher real estate values. Like their mother and aunt and uncles, my sister’s children attend a parochial school a few blocks away. But they don’t walk to school, and neither do their classmates. It’s a different day now.

Sunday, June 10, 2007

The Porch

What’s the most romantic part of a house? Some people would say a porch. Well, 841 N. Maplewood had a great one, and I would wager it was my mother’s favorite part of the house.

Our porch wasn’t a front one or a back one, but a side one that ran at least half the length of the house and overlooked the corner of Laura and Maplewood. We resurrected the porch in spring, like some people open up their summer homes. With its maroon tile, white wicker furniture, and screens that ran from almost the ceiling to more than half way down the walls, the porch was cool on the hottest day. It was the perfect place to sit and watch our part of the world go by.

To be honest, I didn’t appreciate the porch when we lived in the house. But my mother did. “Breakfast, lunch, and dessert,” she listed when I was trying to remember the times she spent on the porch. She would read the newspaper and drink her tea.

During the day, a steady stream of Bradley students and staff passed by the house: Ruthie Keyes, who worked in the library, John Kenny, the physics professor, (he once replied to my husband, his student, who said in frustration during a lab, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” with “Who does?”), Clarence Brown from the counseling department. I wish we could run a tape fast forward through the decades to see all the people who walked down Laura to and from Bradley; it would be a cornucopia of hair lengths and clothing styles.

When I was 16 and in possession of my driver’s permit, my friend Bernadette, who had her license, picked me up along the side of our house in her family’s station wagon. We drove one block to the corner of Cooper and Laura, where Bernadette and I switched places in the front seat. We didn’t drive quite far enough away, because my mom sitting on the porch, couldn’t help but witness this act, shocked at the treachery that her firstborn would engage in. I don’t remember this incident or the repercussions that followed, but my mom assures me she saw the whole thing from the porch.

What easy, fun childhoods many of us who grew up in the latter half of the 20th century had. It wasn’t the same for the namesake of the street that our porch overlooked. In 1864, about 113 years before my driving shenanigans, Laura Bradley, 14, the last surviving child of Tobias and Lydia Bradley, died. According to Allen A. Upton in Forgotten Angel: The Story of Lydia Moss Bradley, one of Laura’s teachers had this to say about her:

“I became acquainted with the family of Mrs. Lydia Bradley in the fall of 1862, and I was an occasional guest at their home. The family then consisted of the father, mother, and Laura, the last survivor of several children. The loss of the other children seemed to have intensified the affection of father and mother for their daughter, and their affection was fully and warmly reciprocated. When Laura entered my school—the old Franklin—in the fall of 1862, she was a slender, vigorous, fair, light-haired girl, ambitious and earnest. She was a generous, amiable and affectionate girl, and always did her best with all work given her to do. Her unselfish generosity and kind disposition made her a general favorite. . . . She was possessed of a dignity and propriety rarely found in one of her age, though full of life and spirit.”

Our porch wasn’t a front one or a back one, but a side one that ran at least half the length of the house and overlooked the corner of Laura and Maplewood. We resurrected the porch in spring, like some people open up their summer homes. With its maroon tile, white wicker furniture, and screens that ran from almost the ceiling to more than half way down the walls, the porch was cool on the hottest day. It was the perfect place to sit and watch our part of the world go by.

To be honest, I didn’t appreciate the porch when we lived in the house. But my mother did. “Breakfast, lunch, and dessert,” she listed when I was trying to remember the times she spent on the porch. She would read the newspaper and drink her tea.

During the day, a steady stream of Bradley students and staff passed by the house: Ruthie Keyes, who worked in the library, John Kenny, the physics professor, (he once replied to my husband, his student, who said in frustration during a lab, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” with “Who does?”), Clarence Brown from the counseling department. I wish we could run a tape fast forward through the decades to see all the people who walked down Laura to and from Bradley; it would be a cornucopia of hair lengths and clothing styles.

When I was 16 and in possession of my driver’s permit, my friend Bernadette, who had her license, picked me up along the side of our house in her family’s station wagon. We drove one block to the corner of Cooper and Laura, where Bernadette and I switched places in the front seat. We didn’t drive quite far enough away, because my mom sitting on the porch, couldn’t help but witness this act, shocked at the treachery that her firstborn would engage in. I don’t remember this incident or the repercussions that followed, but my mom assures me she saw the whole thing from the porch.

What easy, fun childhoods many of us who grew up in the latter half of the 20th century had. It wasn’t the same for the namesake of the street that our porch overlooked. In 1864, about 113 years before my driving shenanigans, Laura Bradley, 14, the last surviving child of Tobias and Lydia Bradley, died. According to Allen A. Upton in Forgotten Angel: The Story of Lydia Moss Bradley, one of Laura’s teachers had this to say about her:

“I became acquainted with the family of Mrs. Lydia Bradley in the fall of 1862, and I was an occasional guest at their home. The family then consisted of the father, mother, and Laura, the last survivor of several children. The loss of the other children seemed to have intensified the affection of father and mother for their daughter, and their affection was fully and warmly reciprocated. When Laura entered my school—the old Franklin—in the fall of 1862, she was a slender, vigorous, fair, light-haired girl, ambitious and earnest. She was a generous, amiable and affectionate girl, and always did her best with all work given her to do. Her unselfish generosity and kind disposition made her a general favorite. . . . She was possessed of a dignity and propriety rarely found in one of her age, though full of life and spirit.”

Friday, June 8, 2007

High School Days

At one time, early in my childhood, kids who lived in the 800 and 900 blocks of Maplewood could go to either Manual or Peoria High School. However, by the time I was in high school—1975 for anyone who’s counting—kids on the Field House side of Maplewood, the south side, were in the Manual district. Those who lived on Maplewood but on the other side of Main Street—the north side—were in Peoria High’s district.

At one time, early in my childhood, kids who lived in the 800 and 900 blocks of Maplewood could go to either Manual or Peoria High School. However, by the time I was in high school—1975 for anyone who’s counting—kids on the Field House side of Maplewood, the south side, were in the Manual district. Those who lived on Maplewood but on the other side of Main Street—the north side—were in Peoria High’s district.Of course, the other choice in high schools then were the two Catholic schools, Academy/Spalding and Bergan. Most of the kids in our neighborhood—the Boesen’s, Keister’s, the younger Mallow kids, the Koperski’s—went to Manual.

My siblings and I went to Academy/Spalding. We lived almost exactly two miles from the downtown campus. During my junior and senior years, on nice days, I would walk to school, often with Bernadette Dries, who lived on Moss. But usually, I caught a city bus that went down Main Street, specifically for the purpose of picking up AOL/SI students. It was called the Special and you would think the time it arrived on the corner of Main and Maplewood to pick us up would be engraved in my mind; I think it was 7:30, but I’m not positive.

There would be anywhere from three to eight kids waiting for the bus. More than a few times, I had to break into a sprint down Maplewood, alerted by those who were already on the corner of bus’s imminent arrival. And also a few times, I would be barely out the front door, only to see the bus pulling away from the corner.

Most of the kids waiting on that corner were from the other side of Maplewood—Cindy Brissette, the Moore’s, the Potts, the Kenny’s—while most of the kids on our side of Maplewood went to Manual. We were used to attending different schools than our neighbors, as we had gone to St. Mark’s and most of our neighbors had gone to Whittier. As we grew older, this difference in schools made more of a difference in our friendships with these kids, not because of any bad feelings, but mainly because we were spending more time now with different people.

I remember the good-natured rivalry that ensued between Kevin Boesen, who lived next door, and me in 1976. Kevin was the middle of the three Boeson boys. I was a sophomore at Spalding and Kevin, a really bright guy, who is now a minister in Hudson, Illinois, was a junior at Manual.

Late in the season, both Spalding and Manual’s football teams were undefeated. Spalding had been blowing out their opponents, and in the second to last game of the year, their record stood at 7-0. Manual was having an equally impressive season and the excitement before this big game was the talk of the school. At our pep rally, all the players sauntered out on the gym floor looking cool and full of confidence—Dave Mischler, John Venegoni, John Girardi, Jim Ardis, Joe Slyman, Don Crusen, Tom George, Ron Mischler, all of whom, I think, were all conference.

A few days before the big game, Kevin was doing dishes in their kitchen. Their kitchen windows were directly opposite ours. He began gesturing through the window at his Manual t-shirt and holding up his finger to indicate #1. I responded in kind, as we pantomimed our messages of school football superiority through the windows. Many of the windows in our house—the landing, some of the bedrooms—matched up with the windows in the Boeson house.

Well, I don’t remember Kevin rubbing it in after the game, and he could have because Manual spanked Spalding 28-0. Ouch! Manual didn't lose until the second round of the state play offs when they were defeated by Danville. Oh well, at least Spalding ended the season by beating our archrival, Bergan.

The 1976 Spalding team plays Peoria High School.

Wednesday, June 6, 2007

Globetrotting on Maplewood

My dad worked at Bradley for his entire career—almost 40 years. During that time, we met a lot of his colleagues. One of them was Curley Johnson, who served as head of security at Bradley University.

Like my dad, Curley had an association with Bradley before going to work there. In Curley’s case, he was one of the first African-American basketball players at Bradley. After he graduated, Curley worked as a probation officer in Chicago before coming back to Peoria.

One of my dad’s responsibilities at Bradley was student discipline, so he had a close working relationship with the head of security. Curley would occasionally stop by our house.

I remember one embarrassing encounter that I had with Curley. Well, I wasn’t smart enough to be embarrassed by it then. Curley was a very friendly, jovial man whom we immediately took a liking to. When I found out that his first name was Curley, I insisted on knowing what his “real” name was. Chomping down on his cigar, he repeatedly told me, “Curley.” I asserted that this had to be a nickname, and feeling like I was being duped, persisted in asking him, “No, really, what is your real name.” Wide-eyed, what could Curley do but insist upon the truth? I think later when I asked my, dad who confirmed that Curley was indeed his real name, I may have felt a bit perplexed but the embarrassment didn’t come until later.

One day, Curley dropped off his young son at our house to stay with us for a few hours. His son, whose given name was also Curley, had the nickname of Boo. Boo was probably about eight or nine years old and we liked him as much as his father. He was quiet and had the most beautiful afro. What else could we do but go across the alley to the Dougherty’s and shoot baskets?

Boo Johnson, of course, went on to have a glorious 17-year career with the Harlem Globetrotters, where he was known as one of the fastest dribblers in the world. I never had any more contact with Boo after a couple of these childhood visits, but like many Peorians, I followed his career through the newspaper.

I remember reading Boo’s remarks to some students at Harrison School. As a Globetrotter, Boo had gotten to do just that and had been all over the world. He told the kids from the south side of Peoria about the homeless children he had seen in some poor countries, children who didn’t have families or food on a regular basis or a school to go to. You have everything, Boo told these kids—running water, teachers, books, a place to sleep. Appreciate and take advantage of your opportunities was the message.

How many times have Peoria’s children from District 150 been told that from such a credible messenger?

Like my dad, Curley had an association with Bradley before going to work there. In Curley’s case, he was one of the first African-American basketball players at Bradley. After he graduated, Curley worked as a probation officer in Chicago before coming back to Peoria.

One of my dad’s responsibilities at Bradley was student discipline, so he had a close working relationship with the head of security. Curley would occasionally stop by our house.

I remember one embarrassing encounter that I had with Curley. Well, I wasn’t smart enough to be embarrassed by it then. Curley was a very friendly, jovial man whom we immediately took a liking to. When I found out that his first name was Curley, I insisted on knowing what his “real” name was. Chomping down on his cigar, he repeatedly told me, “Curley.” I asserted that this had to be a nickname, and feeling like I was being duped, persisted in asking him, “No, really, what is your real name.” Wide-eyed, what could Curley do but insist upon the truth? I think later when I asked my, dad who confirmed that Curley was indeed his real name, I may have felt a bit perplexed but the embarrassment didn’t come until later.

One day, Curley dropped off his young son at our house to stay with us for a few hours. His son, whose given name was also Curley, had the nickname of Boo. Boo was probably about eight or nine years old and we liked him as much as his father. He was quiet and had the most beautiful afro. What else could we do but go across the alley to the Dougherty’s and shoot baskets?

Boo Johnson, of course, went on to have a glorious 17-year career with the Harlem Globetrotters, where he was known as one of the fastest dribblers in the world. I never had any more contact with Boo after a couple of these childhood visits, but like many Peorians, I followed his career through the newspaper.

I remember reading Boo’s remarks to some students at Harrison School. As a Globetrotter, Boo had gotten to do just that and had been all over the world. He told the kids from the south side of Peoria about the homeless children he had seen in some poor countries, children who didn’t have families or food on a regular basis or a school to go to. You have everything, Boo told these kids—running water, teachers, books, a place to sleep. Appreciate and take advantage of your opportunities was the message.

How many times have Peoria’s children from District 150 been told that from such a credible messenger?

Harlem Globetrotter and Peoria native Curley "Boo" Johnson demonstrates his basketball spinning prowess.

Monday, June 4, 2007

Campus Carnival

Basketball games weren't the only events the Robertson Memorial Field House hosted. Rock groups like REO Speedwagon, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and other acts played there in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s. Sometimes during concerts, the naughty, sweet smell of marijuana would waft through the air, tingeing the night with the forbidden.

For many years, the Field House has been home to another event that I looked forward to almost as much as Christmas: the Campus Carnival. This extravaganza was put on by the fraternities and sororities to raise money for charity.

The Field House was transformed into the childhood equivalent of Las Vegas with garishly decorated booths where we tried to win the much-coveted beer holders, beer mugs, beer signs, and—if we really got lucky—beer lights. Talk about marketing to children. Really, the companies probably donated the stuff in deep gratitude for all the business the college students gave them. And, anyway, this was before the days of car seats, bicycle helmets, and no drinking while pregnant. In some ways, children are physically safer now, but emotionally and psychologically, childhood seems under assualt. Beer paraphernalia seems practically innocuous compared to MySpace, gangsta rap, and R-rated primetime programming.

I remember one year during the Carnival after I had spent the amount of money I or my parents—I can’t recall which—had allotted to the festivities. I would race back and forth between our house, which was kaddy corner from the Field House, raiding the stash of 50 cent pieces, kept in a cigar box, that my grandfather gave me, like an addict on the Par-a-dice hitting the ATM machine. For all the anticipation and fun of the carnival, I had a bad feeling walking home empty handed or with stuff that somewhere deep inside I recognized as cheap, having depleted my Eisenhowers and Kennedys. In fact, I would like to apologize now to my grandpa in heaven for squandering these precious coins.

A couple of years, my dad was a participant in Campus Carnival. He volunteered to be a target for a dunk tank and another water game. I had strange and mixed feelings watching kids I knew, as well as some college students, do their best to send my dad plunging into the tank or soak him with water, which, if the above picture is any indication, he seemed to enjoy.

Saturday, June 2, 2007

The Bard of Maplewood

I remember standing alone in front of my house after a deep, winter snow. The world evoked Robert Frost’s poem, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.

Along came a man, walking down the middle of the street where the snow was packed. He was wearing a trench coat, and a fedora capped his head, above his ruddy face.

It was Daniel Webster Smythe, a poet.

I knew this because my parents had told me, and, like my father, Mr. Smythe worked at Bradley University. I don’t think I ever spoke a word to Mr. Smythe in my whole life, though his friendly wife Ruth, with the sound of Cape Cod still in her voice, occasionally visited my mother. She would take mom to their book crammed house, five places down from ours, looking for some thing or another. The Smythe’s had two children, a boy and a girl, who were grown by the time we came along.

So, all I really know of Daniel Smythe is what I learned reading his poems and bits of public information about him. He was a widely published poet with poems in more than 100 publications, including the New Yorker and Harper’s. He won the Annual Award of the Poetry Society of America in 1940 and many other prizes during his life.

Before his academic career, Mr. Smythe worked on a farm in New Hampshire and on a wildlife sanctuary in New York, which perhaps explains why so many of his poems have nature as their theme. He served in the armed forces during World War II, and he came to Bradley in about 1949 to teach American literature and creative writing.

Daniel Smythe was praised by many influential poets, including Robert Frost, about whom he wrote a book, Robert Frost Speaks.

The book of poems on my shelf entitled, The Best Poems of Daniel Smythe, is inscribed, “For Ed & Mary King With best wishes, Daniel Smythe Thanksgiving 1974” He died seven years later.

I didn’t know when I saw him walking down the street that I would one day take classes in creative writing—poetry no less—as a graduate student at Bradley. Poetry—it’s a word that makes a lot of people, including me, a little nervous. There’s a kind of mystery about it. I think poetry has something to do with trying to see the world with fresh eyes and translating the observations into fresh language, though this is a stale way of putting it.

Well, as the saying goes, “I know what I like.” Here is a poem from Daniel Smythe’s anthology. It’s not one of his many award winners, but I like it.

THE BEACH

Landscape,

sea-bird,

shell shape,

sea heard.

Fog snug,

beach rose,

rockweed rug

grows and grows.

The snail hut,

word-lost shore –

this is what

I am looking for.

Along came a man, walking down the middle of the street where the snow was packed. He was wearing a trench coat, and a fedora capped his head, above his ruddy face.

It was Daniel Webster Smythe, a poet.

I knew this because my parents had told me, and, like my father, Mr. Smythe worked at Bradley University. I don’t think I ever spoke a word to Mr. Smythe in my whole life, though his friendly wife Ruth, with the sound of Cape Cod still in her voice, occasionally visited my mother. She would take mom to their book crammed house, five places down from ours, looking for some thing or another. The Smythe’s had two children, a boy and a girl, who were grown by the time we came along.

So, all I really know of Daniel Smythe is what I learned reading his poems and bits of public information about him. He was a widely published poet with poems in more than 100 publications, including the New Yorker and Harper’s. He won the Annual Award of the Poetry Society of America in 1940 and many other prizes during his life.

Before his academic career, Mr. Smythe worked on a farm in New Hampshire and on a wildlife sanctuary in New York, which perhaps explains why so many of his poems have nature as their theme. He served in the armed forces during World War II, and he came to Bradley in about 1949 to teach American literature and creative writing.

Daniel Smythe was praised by many influential poets, including Robert Frost, about whom he wrote a book, Robert Frost Speaks.

The book of poems on my shelf entitled, The Best Poems of Daniel Smythe, is inscribed, “For Ed & Mary King With best wishes, Daniel Smythe Thanksgiving 1974” He died seven years later.

I didn’t know when I saw him walking down the street that I would one day take classes in creative writing—poetry no less—as a graduate student at Bradley. Poetry—it’s a word that makes a lot of people, including me, a little nervous. There’s a kind of mystery about it. I think poetry has something to do with trying to see the world with fresh eyes and translating the observations into fresh language, though this is a stale way of putting it.

Well, as the saying goes, “I know what I like.” Here is a poem from Daniel Smythe’s anthology. It’s not one of his many award winners, but I like it.

THE BEACH

Landscape,

sea-bird,

shell shape,

sea heard.

Fog snug,

beach rose,

rockweed rug

grows and grows.

The snail hut,

word-lost shore –

this is what

I am looking for.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)